Does the client know best? The Dunban-Müller Effect

This time it’s personal...

The anecdote I am about to paint with words has affected me so much since its happening that this is perhaps the 100th time I’ve told it.

Back in 2021, a much younger, brighter-eyed, less jaded, and most importantly, younger version of myself presented some of my creative brand designs to my boss then-boss. Upon seeing the six logos I’d designed for him that day, he had some interesting thoughts… After a very defensive conversational tennis match, he hit back at me with a line that has since become cognitively latched into my neurochemistry:

“Ahhh, but you see, Willem, you’re looking at these creatives from the perspective of an expert, so of course you think the more sophisticated brand design is the better option.”

…

Now, in my professional (yet extraordinarily humble) opinion, my granted expertise in the field in which at that point I’d studied for seven years, was the exact reason why my perspective should have been taken on board. I’m not sure how many other professions you could make this same argument against; “Well, you’ve been a successful heart surgeon your whole life; I don’t see why I should trust you to perform this operation…”

Are there other professions in which, typically, the more experience you possess the more of a disadvantage you’re seen as having? Coder? Rocket Scientists? Professional footballer? Hadron-Collider Technician?

Creative cats and designer dogs

It’s coming to my attention that this article is rather hard to write without the content coming across as incredibly personal. Perhaps that’s unavoidable.

Just like the chaps sitting to my left and right, I, as a graphic designer in a marketing agency, have been in many a situation where a brand design I’ve created – something that I loved – has been adapted so much that by the time of its finishing, I no longer consider it recognisable as my own work.

Two perspectives have been unearthed in this article thus far. They manifest themselves in semi-oppositional needs. The two needs from the two perspectives are as follows:

- The client needs a design they feel is right for their business.

- The graphic designer needs to be able to make creative outcomes they deem appropriate to the client's marketing.

When written down like this, things seem quite simple. The client needs creative brand design done, and the designer needs someone to do creative brand designs for. Surely this should be be a match made in heaven!?

However, as usual, the situation described is a lot simpler in theory than in practice. What should be a joyous pairing is often the beginning of a very intense period of debate, deliberation, and compromise.

People are complicated. What one person wants is almost certainly destined to clash with what another person wants – and most people really, really don’t like compromise.

The two colliding needs of client and graphic designer are actually the oil and flame required to create a chain reaction of dramatic potential. In this state of chaos lies the very real possibility for confusion, disagreement, and a whole lot of flying blindly.

However – and most importantly – as always with chaos comes the potential for change and growth. It offers the chance for both client and designer to arrive together at an end point, with a finished product that neither expected but both can be equally proud.

Sometimes, this happens, and when it does, it is glorious. Then there’s the flipside of the coin that goes something like this:

The brief is given by the client.

The designer does the work.

The designer presents the work back to the client.

The client has one or two things they want changing about the design…

And here’s the tricky part. We’re at the stage when one of two things is going to happen. Either the designer finds the comments fair – or better yet, completely just and right and as a result modifies their design post-haste without complaint, glad that the change was brought to their attention… Or (and this is much more likely), the designer will find the requested amendments to their work – their creative brand design, their baby – unnecessary, too drastic, or just wrong. The change is made, grudgingly, and a strained working relationship is established.

Shortly after this exchange, an attitude problem emerges on both sides of the debate. The client comes across as deliberately obtuse and unknowing, unwilling to listen. The designer comes across as overprotective and petulant, unwilling to compromise.

At this point, an awkward tension exists between client and designer. The client wants what they want to be designed, but that does not always align with what the designer thinks that the client needs. This is the heart of the frustration.

Expertly done

The time has come for me to postulate. As web graphic designers, when it comes to visuals, we do know best. This is why we’re employed to do the creative brand design in the first place; if anyone could do our job, they would.

We are experts in visual communication. Our sole purpose is to see a world made just slightly more beautiful than it was before. We are the guardians who stop drop-shadow typography, garish gradients, cluttered page layouts, and comic sans from getting through the gates of print and digital design. Or, to put it more directly, we are there to make sure our client’s creative brand design doesn’t look terrible and, provided both parties are lucky, ensure that their graphics look good...

The creative nature of brand design - and art in general - makes our profession more subjective and therefore leaves it more justifiably open to criticism. However, that doesn’t always mean that a client’s critiques are going to be productive. This is why we look personally offended when we hear feedback such as: “Well, I support Aston Villa, you see, so could you change the whole design so it’s all in claret and blue?” (An amendment I’ve actually had before…)

We see our job as trying to help our clients do something they cannot; graphic design. Which is why we’re shocked when we do present our ideas to the client and they hit us with an explosive twist!; Over the course of the meeting, they too have become expert graphic designers in marketing and have decided they don’t like the font, the logo, the colours, and are not particularly interested in hearing any argument in the defence of the idea as it was presented to them – they just feel the design needs to “pop” more…

The untrained graphic designer as an advantage

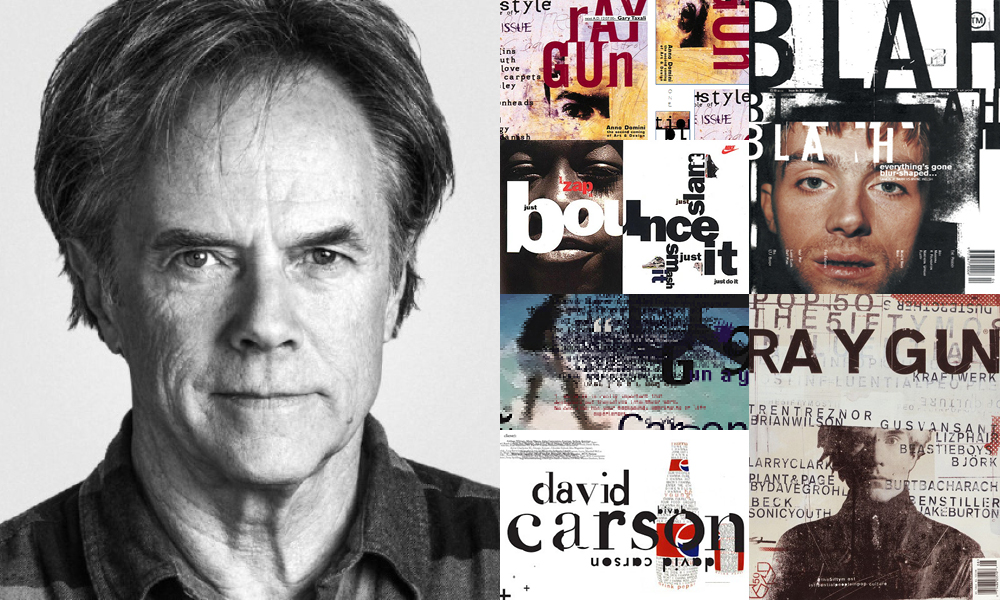

An article about people untrained in design giving critiques on design would not be properly balanced without an admission on the part of this writer/designer; some of the world’s most famous graphic designers of the 20th Century have no formal graphic design training whatsoever. People who have catapulted themselves to legendary status in the annals of design history – people like Wally Ollin’s, Adrian Shaughnessy, David Carson and Tibor Kalman, all famously never received any kind of formal training in graphic design.

Take David Carson in particular. His punkish, DIY, no-rules collages inspired by his youth as a California-surfer made metaphorical waves in the 90s that completely disrupted the rigid design conventions of the time. Carson receives a lot of flak in the design community. His work is regarded as immature. Often admired by fledgling designers, only to be cast aside like a toy from one’s childhood when they grow up to enjoy more mature things.

Carson’s design philosophy was invented pragmatically and practically (At first). While eventually shoe-horning his collages into every project he would ever do, at first, they were completely appropriate for the independent surfer scene in which he honed his blade as a graphic designer.

Carson’s designs express rebellion, but they express it over and over again to the extent that people have now become tired of listening to his talk of rule-breaking and now wish that, perhaps, he’d break a few rules of his own.

Fair enough, perhaps. No one is without their faults. But he remains an important figure all the same as he did something that no trained graphic designer could do. He looked at things from a fresh perspective. He reminded us that this is a creative discipline and that there simply are no rules.

In this very specific case, it was indeed his lack of traditional training that put him at an advantage. He could see what the trained graphic designer could not.

The Dunban-Müller effect

The thing is, a lot of non-experts in design seem to believe that this lack of knowledge is an advantage to them in the same way it was to Carson. This is the same instinct that possesses someone to say that their three-year-old could have done that painting while visiting the Louvre.

However, Carson wasn’t an accountant who needed a new logo designed. Despite not having a degree in graphic design, Carson shares a trait found in all graphic designers that is most likely lacking in the logo-less accountant; Carson, over the years, while doing his job, acquired a lot of practice doing graphic design… Yet, while the graphic designer has no interest in stepping into the accountant’s realm of mathematics, (a realm in which the accountant has lived in for years and grown to be accustomed to) the accountant can approach the graphic designer with a relative amount of comfort, knowing that creativity is subjective.

When Someone knows little about design and is trying to be different, the call to use Comic Sans and Impact Extra Bold becomes very strong… They create a switcheroo in their mind in which their own absence of knowledge on graphic design is in fact their advantage. They can see things in a new and fresh light that the graphic designer has no hope of being able to comprehend. Meanwhile, the graphic designer struggles along, body weighed down and vision clouded by years of study and industry experience that amount to nothing more than a stone around their neck, holding them back from ever truly being able to design to the same high standards someone with no training ever could…

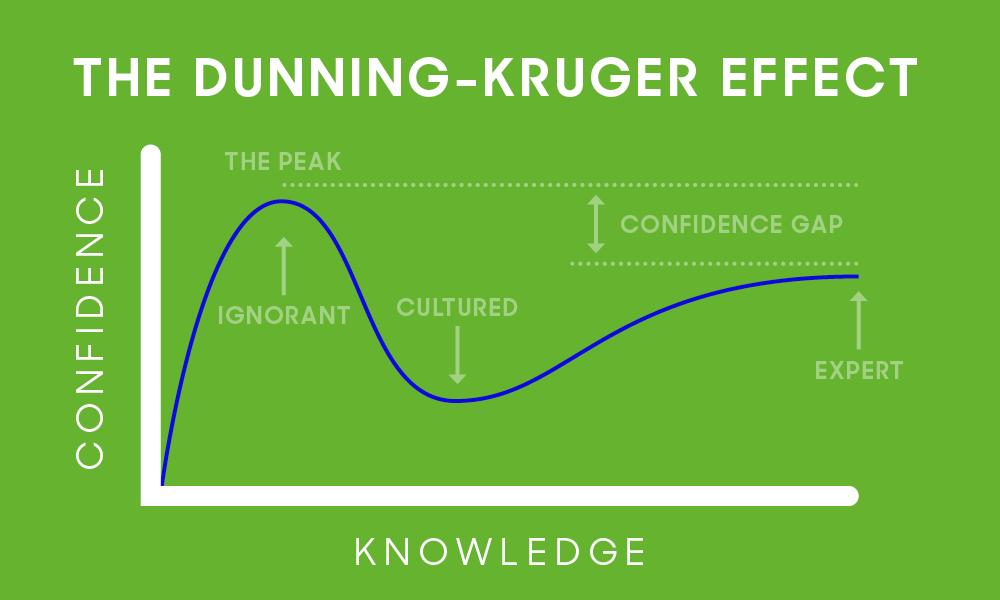

This is called the Dunning-Kruger effect. It’s the theory that the less you know about something, the more you assume you know about it due to being totally unaware of just how much remains to be learnt on the subject.

A graphic designer is victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect on as many subjects as most, but not graphic design. About that they know plenty. However, it’s interesting to note that while immune to one form of cognitive illusion, the graphic designer may be struggling from another.

The Overconfidence effect is a cognitive distortion that makes people overestimate their own competence and the significance of their own profession within the context of the rest of the world. I remember being particularly guilty of this as a second-year graphic design student when I wrote a semi-manifesto entitled “A world without graphic design”. The basic premise of the essay was to highlight the problems that would occur in a world without signage. My favourite example being that a lack of toilet signs would mean no-one would know where to go for a wee in the pub. The essay did not receive a particularly high mark…

Conclusion

It was pointed out to me before I sat down to write this article on the designer-client relationship, that if it were written in my usual sarcastic, snide tone of voice, it may not come across particularly well. I agree. And if there’s one thing I’ve learnt from writing this article, it’s the importance of mutual respect.

A cliché though it is, designers and clients need each other. Designers need clients to give us work to do, and clients need designers so their logo isn’t reduced to a scribble that their friend did for them on a napkin because, “they’ve got an eye for this sort of thing”.

While it may be true that clients can be prone to belittling design choices, meddling unnecessarily, and graphic-design cowardice, graphic designers themselves should take equal part in blame. We can be obtuse, snobbish, and often lack the communication skills required to back up our ideas effectively.

An ideal working relationship between client and designer would involve both parties working together and respecting each other’s expertise; a relationship in which good communication and humility leads to better work and the prospect of working together again. Basically, we need to trust in each others expertise enough to let allow both parties to do their jobs properly.