2024 is a creative’s existential limbo – Change my mind, or is the modern era a good time to be a creative?

Part 2 –

Welcome back to part 2 of the stream-of-consciousness, hellscape-circus that is me trying to unravel my thoughts on the relationship between creative culture and how it is impacted by the digital age.

In the last part, (which was only over a year ago so I am sure you remember!) I complained how my Instagram feed hated me, why that is a symptom of a design landscape on a steep decline and how an art style’s reputation was dragged through the mud because of guilt by association.

So, what are we going to do this time?

Together, me and you *locks eyes establishing trust and brotherhood* are going to expand further on the context of the digital age and then explore the consequences it lays down at the doorsteps of creatives worldwide, like a digital stork!

Capitalism – The university student’s Bogeyman

Unpopular opinion for a former art student, but I like capitalism. I like buying full-fat Coke; I like it when Mark Zuckerburg steals my browsing history; I like the thought that, if I’m ever going to be able to afford a house, I’ll have to win the lottery first, and I love being told that it’s all my fault because I don’t work hard enough. Look, just deal with it. It’s capitalism. It’s fine. We’re all fine. We’re all FINE. Got it?

However… If I had to leverage one reluctant criticism at the doorstep of capitalisms’ mega mansion in the Canary Islands, it might be…

Capitalism encourages really boring creative work!!!

Something I have noted more often than I would have liked to have noted, is that once a new benchmark has been established in creative trend, that benchmark outstays its welcome long past being described as rude…

Let us briefly return to Corporate Memphis as an example.

A year ago, I was able to gather so much evidence about the public disdain for Corporate Memphis, or “the big-tech art-style”, that I was able to write an article about it. Shockingly, despite all the evidence I found, leading me to believe that this was a universally loathed style of illustration, it is still being used today – nearly 12 months later! In fact, it’s probably more commonplace now than it ever was before.

One might be tempted to believe that if designers and consumers alike are in agreement about their repulsion for one art-style in particular, they might stop using it in their work… Well, if you thought that as well, then apparently, we would both be as dumb as each other. If anything, the “the big-tech art-style” has cemented itself as a viable arrow in the quiver of the collective-creative-consciousness. It has done something fascinating; Corporate Memphis has absorbed so much malice that a year and a bit after writing my article, it has emerged from the desert of hate, enlightened.

That to me begs a question; How could an art style so detested survive? Why didn’t designers just use something else?

The answer… Unfortunately… Is boring…

Because it makes money.

Told you this bit was about capitalism... Corporate Memphis is used by a plethora of big-tech, property, and fintech companies. Most notably, AirBnB, Hinge, Airtable, Google, Youtube and the big Scarface of capitalism himself, Facebook.

Evidently, these companies know something about Corporate Memphis that we don’t. They must be aware that this vague gesture in the direction of humanism is actually quite a viable marketing strategy. It’s a safe pair of hands not just visually but fiscally too.

Now… Say you own an aspiring Fintech start up. And you’re looking at the branding of more established, more successful Fintech companies, companies whose names people have actually heard of, companies who you aspire to be like, and you see the art style they use… But! And it’s a big but: you don’t just see the art-style in question once. You see it on every Fintech company you look at. You’d be forgiven for thinking that this art-style is the one you need to use to signal to potential customers: “THIS IS A (SUCCESSFUL) FINTECH COMPANY!!!”.

This idea could potentially scare any director into forcing their designer to conform to the narrow visual confines of what the sector has come to be known for.

About this phenomena of trend-bullying clients away from making bold design decisions, I have a few thoughts:

Thought #1: I understand:

It’s scary to do things differently. It’s scary to go in alone. It’s scary to venture into uncharted territory, so I kind of get why people briefing their designers wouldn’t want their branding to run the risk of having connotations with anything other than what their customers already know about that industry.

This is similar to the thinking outlined in the UX principle known as Jakob’s Law, which states:

“Users spend most of their time on other sites. This means that users prefer your site to work the same way as all the other sites they already know.”

Or, if you’re a FinTech company, you probably want people to look at your stuff and see what they already associate with FinTech companies. You might want your potential customers to use as little mental bandwidth as possible to figure out what your company does and how it provides similar services to companies in the same sector that they may already be familiar with.

That makes perfect sense.

However, empathy aside, (ahh, my specialty!) there is a problem with this that I find glaringly obvious…

Thought #2: Good Design is Brave:

Simple as…

Playing it safe may be… Well… Safe… But surely a better brand strategy has always been to stand out from one’s market competitors rather than blend in?

If a potential client looks at the websites of 10 FinTech companies and 9 of them use Corporate Memphis because that’s what FinTech companies just do, well, do you not think that by even the 4th time a potential investor drags their already glazed-over eyes onto a website with Corporate Memphis yet again, that they are already going to be dreadfully bored of seeing the same derivative drivel soullessly smeared onto the screen? Do you not think that by the time they get to the 10th website that has its own visual identity they are not only going to be refreshed but also galvanised? Intrigued, perhaps?

If you don’t trust me, that’s fine… But what if it weren’t just me that thought this strategy was a better one than just blending into the crowd? What if it wasn’t just any company that shared my philosophy, but the company with maybe the most effective branding in history? What if it were Apple?

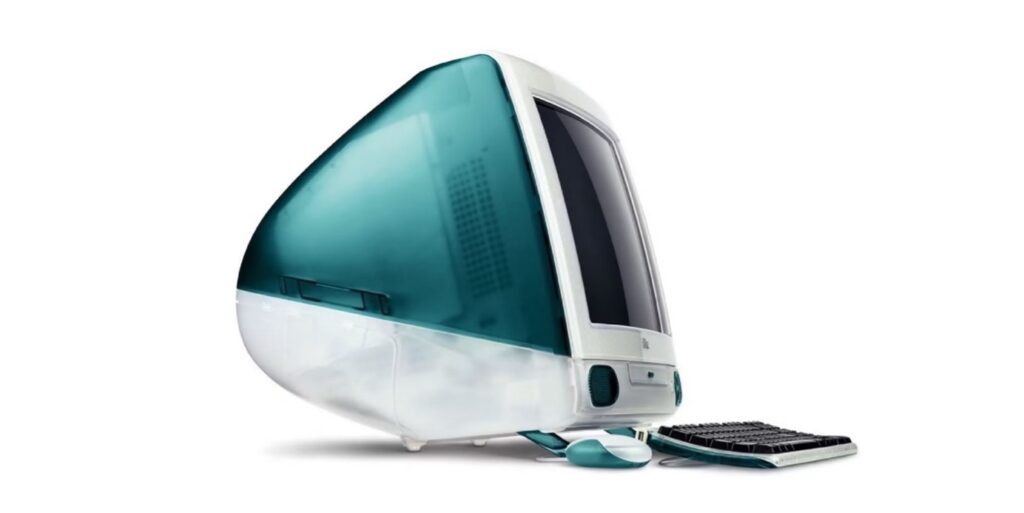

Apple could have easily not released the iMac G3 in 1998. It could have gifted the world another forgettable, grey box you keep on your floor attached to your forgettable, square monitor… They could have easily done that…

INSTEAD, THEY RELEASED THIS BAD BOY!!!

Woah!!!

In a world of whirring grey boxes attached to monitors, Apple decide to launch a space-ship pod thing!

Flashforward 25 years and they have people camping out overnight in tents waiting for the release of the new iPhone as if they were waiting to be first to see Morbius 2…

Apple made their computer as different to all contemporary computers as they possibly could, and the impact was only positive. Apple is now considered one of the coolest, sleekest, most well-developed brands in the world and Microsoft is not…

Think differently!

The first Conclusion

For a change, I can sum up more thoughts about capitalism’s effect on creativity rather concisely here:

- If a visual style makes money or is used by a successful company, other companies will emulate it.

- This perpetuates an unfortunate cycle of prolonged visual trend.

- This discourages design being influenced by anything other than a limited number of references / sources.

- This results in design styles becoming ubiquitous and reduces the chances of seeing experimental design out in the wild.

The thing I find most unfortunate about this is that in an age where any designer has the potential to be influenced by more design than ever before, a world in which they can literally access the entire history of graphic design through a device they keep in their pocket, there is somehow less variety in the design you see every day than ever before.

Why else could this be?

Well, it’s funny you should ask, because in my next section, I might cover just that…

Echo Chambers & Algorithms

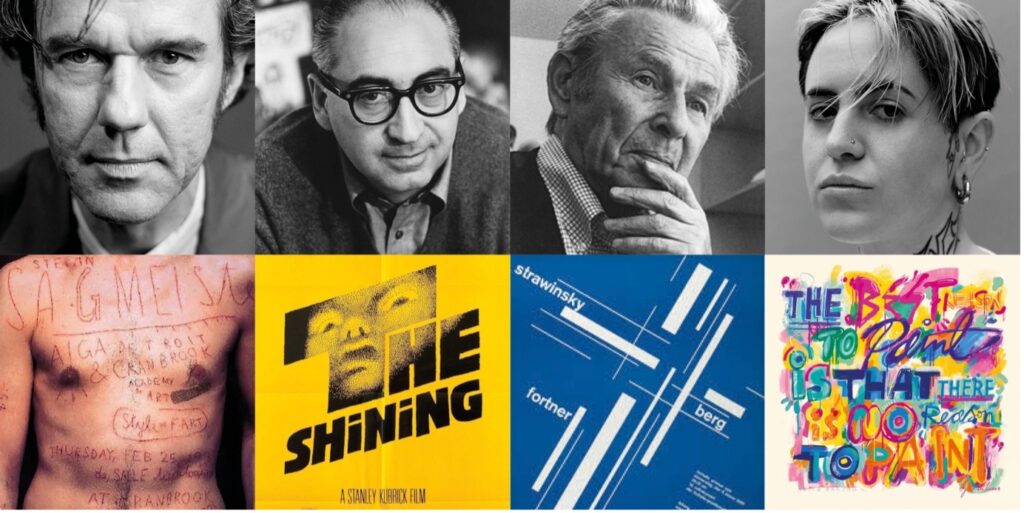

The internet is powerful. Today, any designer can easily google Stefan Sagmeister, Saul Bass, Josef Muller-Brockmann at will. Not as long as we’re being constantly tricked into using addictive apps with the sole purpose of harvesting our data. Why would you even bother taking all that time, and effort, and time, and effort, to lift the page of a book about design from the 50s, when you could just go on Instagram and see what’s at the top of the #GraphicDesign page?

When I was at university, it was apparent that Instagram and Pinterest sat together, atop the throne of design influence. The modern-day, digital-power-couple.

Now, don’t get me wrong, these applications are excellent for the proliferation of design content. It’s easier than it’s ever been to enjoy the work of others or to share your own. However, that is just one positive, afloat on a sea of negatives.

Instagram and Pinterest dictate what is shown to the general public through what is often all-mightily described as “The Algorithm”. Now… the Algorithm, doesn’t seem to care nearly as much about the design reference economy as I do. Instead, the algorithm repackages aesthetics, vibes, and “cores” back to us lowly algorithm-enjoyers based on what we and what other people have already been viewing. Thus, you get the phenomenon known as the Echo Chamber theory, which postulates that once someone has made a habit of viewing certain types of content, the algorithm will feed them more of that same content. This locks one into an incredibly narrow view, a digital world shaped of their own likes and biases.

This creates the same problem as outlined in the previous section on Capitalism. Just as how if something makes money, you will see it again; if something gets views, you will see it again. Thus perpetuating the algorithmic cycle. If everyone is drawing their design reference from the same DNA pool, (Instagram, Pinterest, Behance, Medium, dribble, etc) a DNA pool that’s been chosen for us by the Algorithm, I might add, then everyone’s inspirations and influences will come out similar. As creatives, by virtue of us being who we are, we are going to do our best to put our own “spin” on these styles. But, if you are emulating a style, then unfortunately there is only so much spinning one can do to stop your work from contributing to the algorithm’s zeitgeist.

The problem here lies in the passive absorption of content that social media encourages. While one can google Stefan Sagmeister, Saul Bass, Joseph Muller-Brockman or Aries Moross any second they want to, it is much more likely that a designer is going to see the design that the algorithm has targeted them with that day. In the pre-internet era, (I was not even born then) the reference pool created by university libraries and public libraries never algorithmically dictated the books you were allowed to see, it meant that a designer looking to get some inspiration had to be a lot more conscious and a lot more intentional about what they were going to decide to look at. It wasn’t passive absorption; it was active studying.

The Second Conclusion

Regrettably, this can be summed up in an equation very similar to the first one:

- If a visual style is seen by enough people, enough times, the algorithm will artificially extend its reach.

- This perpetuates an unfortunate cycle of prolonged visual trend.

- This discourages design being influenced by anything other than a limited number of references / sources.

- This results in design styles becoming ubiquitous and reduces the chances of seeing experimental design out in the wild.

I hope that this section and the previous one have done a good job of establishing the unfortunate pattern developing; modern technology allows the creative process to get stuck in ruts…

To stagnate…

Or, and perhaps most unforgivably of all, to be boring…

Adobe – The Designer’s Bogeyman

This section is not only about Adobe. I just liked that title and how it was a callback to earlier. It’s more about the tools designers have come to use, and how in the digital era, they influence the way designers work and how it doesn’t usually encourage creative prosperity.

A huge theme throughout this article is the idea of getting stuck. Be it by habit, trend or forces beyond our control. Yet again, this idea is appropriate. Because as designers, whether one follows trends or not, whether one uses the algorithm for design inspiration or not, I can guarantee one thing with near 100% accuracy; one uses the Adobe products for 95% of their design. Adobe has over 33 million subscribers to its paid “Creative Suite” service and 90% of pro creatives worldwide use Photoshop. A lot of us use Adobe, is my point.

This is not a bad thing… Per say… Why would you use a sharp rock and a tree when a pencil and paper works so much better?

Adobe has made the best set of products in the world right now for the digital creative process. If there was creative suite on the market capable of rivalling Adobe, we would be using it, but there is not.

However, this has created a slight problem; Adobe has created a digital-creative-process-funnel that we as designers, illustrators, film makers, video editors, artworkers, etc, all have to go down to complete our work. Adobe’s products are practically industry standards for the design community. This means, everything we do, we have to do it Adobe’s way. Adobe’s functions, Adobe’s user interface, Adobe’s Software updates, Adobe’s font libraries, Adobe’s presets, Adobe’s strengths, Adobe’s weaknesses…

Adobe’s house, Adobe’s rules…

And we all live in their house…

I make it sound dire and yet it isn’t. Adobe allows designers to do incredibly varied work. Making the point that the popularised use of Adobe products has enforced the creatives who use them to work in a certain way is like saying that roads have enforced the people who use cars to drive in a certain direction… You don’t say…

Having said that…

There is very little room for experimentation when driving one’s car. (Thank God) Roads are narrow, and you can only go the same way as everyone else in your lane.

Is it a coincidence that in an age where the variety of design is at an all-time low, everyone is using the same tool? It can’t be. While it is entirely possible to conquer Adobe, to master it and not be confined by its influence, it’s much more likely that one will succumb to it. Designers are expected to be “proficient” with Adobe products, not revolutionary. We are meant to know how to use them, and there are most definitely correct and incorrect ways to use them. Adobe products come with specific feature sets and tools that by their very nature, define the parameters within which a designer can do their work. Some of these tools and features are easier to master than others, this can lead to their overuse or saturation.

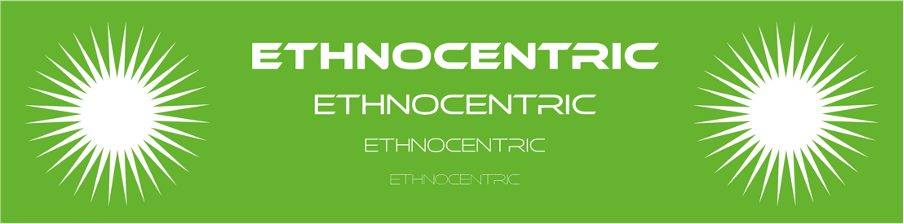

Personally, I am getting tired of seeing the Ethnocentric font family and this weird shape everywhere…

What does that even mean?

The sole reason one comes across this shape so frequently in graphic design nowadays is because it is easy to make; a few clicks on illustrator, that’s it… Ethnocentric, meanwhile, is readily available to download for free on Adobe’s Font archive…

This leads me to a story that actually happened inside of this studio, not a meter away from where I am sitting now, in the design department of Formation. While checking through a website design we were making for a new client, the designer to my left said, in a thick Romanian accent; “If I see another Google font, I think I am going to cry.” To which the designer to my right of me said in a thick Birmingham accent; “Yeah, but they’re good web standard fonts…”

Through this story, we can see the tension. While using a non-Google font would have allowed us more creative opportunities, using a Google font ensured easier usability, at the cost of a smaller pool of fonts to choose from. Our choices were narrowed due to the technology we were using. It was made inconvenient for us to deviate. It was made inconvenient for us to be creative. Uh oh.

The Third Conclusion

This, again, can be summed up with the formula we have developed:

- The technology used by graphic designers encourages certain choices and methods, thereby making our work look a certain way.

- This perpetuates an unfortunate cycle of prolonged visual trend.

- This discourages design being influenced by anything other than a limited number of references / sources.

- This results in design styles becoming ubiquitous and reduces the chances of seeing experimental design out in the wild.

Oh dear…

The Final Conclusion

The big theme that has sprung up all over this article is influence and I think also perhaps coercion. As creatives, we are all influenced by forces beyond our control, forces larger than life, forces that are more like abstract entities, gods of our time, than anything visible or tangible. These entities, be they Capitalism, the Algorithm, Adobe, etc, all force creatives in one direction. We are at their mercy and are forced into playing by their rules.

- If we don’t play by Capitalism’s rules, we go homeless.

- If we don’t play by the Algorithm’s rules, we lose our community.

- If we don’t play by Adobe’s rules, we lose the means to do our job

In a previous context, there was space for a creative to be an individual. Pre-digital-age, you weren’t funnelled towards certain art-styles, certain sources of inspiration or certain tools. There was no funnel.

There was less, but you could do more with it.